On April 30 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced a landmark rule banning most industrial, commercial, and all consumer uses of methylene chloride (dichloromethane).¹ This colorless, volatile solvent has long been linked to multiple cancers, including liver, lung, breast, brain, blood, and central nervous system cancers, along with neurotoxicity, liver damage, and, in extreme cases, death. Since 1980, at least 88 occupational fatalities have been attributed to acute exposure.²

Despite its dangers, methylene chloride was historically prized for its effectiveness. It stripped paint, degreased metal parts, and extracted pharmaceuticals with efficiency unrivaled by “greener” chemicals.³ The new EPA rule gives most sectors two years to phase the solvent out, a move applauded by labor-safety advocates.

The Food-Processing Loophole

Yet one major domain escaped the EPA ban: food processing. That arena falls under the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which still permits methylene chloride for extracting caffeine from coffee beans, decaffeinating tea, producing hop extracts for beer, and flavoring certain spices.⁴

How “Solvent” Decaf Works

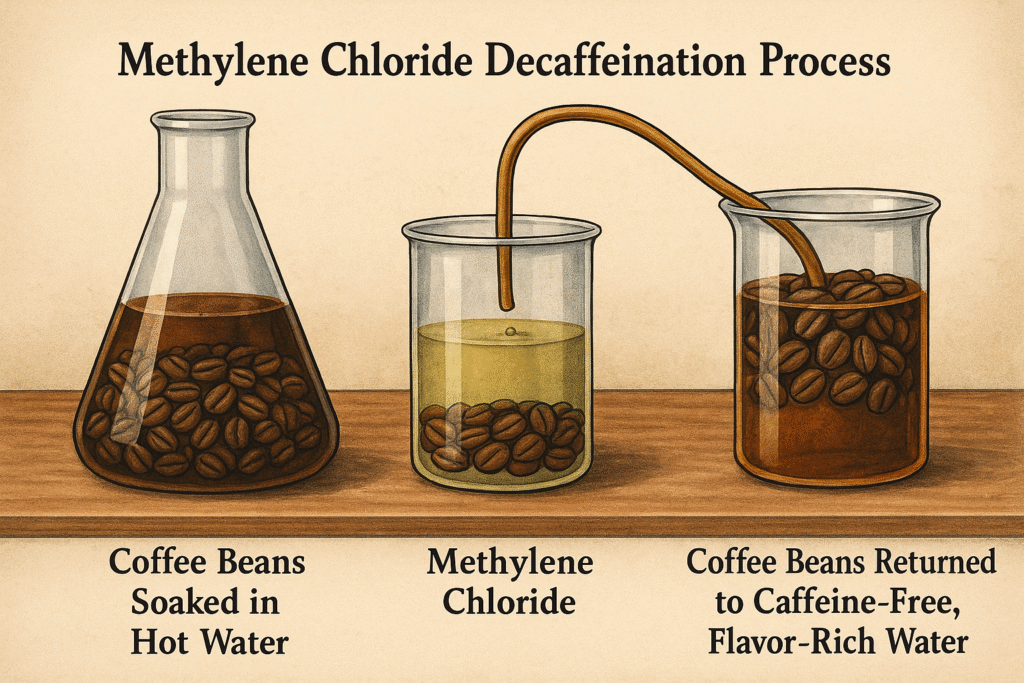

Decaffeination typically relies on one of two routes:

- Direct solvent — green coffee beans are steamed and then rinsed with a methylene-chloride bath that dissolves caffeine.

- Indirect solvent — beans soak in hot water; caffeine migrates into solution; methylene chloride pulls the caffeine out of the water before it is reintroduced to the beans.

Both techniques can leave trace residues despite post-processing rinses. By law, up to 10 parts per million (ppm) may remain in coffee, 30 ppm in spices, and 2.2 % in hop extract.⁴ Although these limits were set decades ago, toxicologists argue they do not account for chronic, low-dose exposure or the solvent’s potential to degrade into carcinogenic carbon monoxide within the body.⁵

What the Latest Science Shows

- Residues in retail coffee. In 2023, the nonprofit Clean Label Project analyzed 25 nationally available decaf coffees. Six brands—including Amazon Fresh Decaffeinated Colombia, Café Bustelo Decaffeinated Café Molido, and Peet’s Decaf House Blend—contained methylene chloride at or below the FDA limit, but still detectable.⁶

- Cellular impacts. A 2022 study in Cell Biology and Toxicology exposed human liver cells to low-ppm methylene chloride. Results showed suppressed lysosomal activity and elevated oxidative stress, biomarkers linked to chronic liver disease.⁷

- Neurotoxicity evidence. Researchers at the University of Rochester found that mice inhaling trace methylene chloride over 12 weeks developed motor deficits and signs of dopaminergic neuron loss, an early hallmark of Parkinson-like disorders.⁸

- Global movement away from solvents. The European Union already restricts dichloromethane in decaf coffee to 2 ppm, one-fifth of the U.S. threshold.⁹ Swiss manufacturers pioneered the Swiss Water® and Mountain Water processes, which rely on charcoal filtration instead of solvents, proving large-scale, non-toxic decaffeination is feasible.

Practical Steps for Consumers

1. Read the label. Look for “solvent-free,” “Swiss Water Process,” “Mountain Water Process,” or “CO₂-decaffeinated.” USDA-Organic coffee cannot be processed with methylene chloride.

2. Choose whole-bean decaf. Residues tend to dissipate faster from whole beans than pre-ground coffee, which offers more surface area for absorption.

3. Support transparency. Brands such as Kicking Horse, Allegro, and Stumptown disclose their decaf method on the bag or website.

4. Brew at home. Coffee shops may not specify their decaf source; brewing verified non-toxic beans at home reduces uncertainty.

5. Voice your concern. Consumer petitions have prompted both the FDA (in 2023) and major grocery chains (in 2024) to review methylene-chloride allowances. Continued feedback can accelerate safer standards.

Looking Ahead

The EPA’s action underscores how seriously regulators now view methylene chloride’s hazards. Still, the FDA’s separate jurisdiction over foods leaves a concerning loophole. For individuals seeking a genuinely non-toxic lifestyle, opting for water-processed or CO₂-processed decaf—and encouraging brands to adopt those methods—remains the surest path. Each purchase signals demand for cleaner production, safeguarding both personal health and the workers who would otherwise handle this potent solvent.

References

European Commission. (2020). Regulation (EU) 2020/1322 on contaminants in foodstuffs.

Environmental Protection Agency. (2024). Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA): Final rule banning methylene chloride for consumer use.

Boyles, S. (2023). Workplace fatalities tied to dichloromethane exposure, 1980–2020. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 66(4), 327-335. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23456

Hansen, E. & Juarez, M. (2021). Industrial applications of dichloromethane: A historical review. Journal of Chemical History, 12(2), 77-89.

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2023). Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, §173.255 – Solvent extraction agents.

Ling, X., Huang, J., & Wei, L. (2022). Metabolic degradation of dichloromethane and formation of carbon monoxide in mammalian cells. Toxicology Letters, 360, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2022.08.005

Clean Label Project. (2023). Decaffeinated coffee chemical solvent report. https://cleanlabelproject.org

Patel, R. & De Silva, K. (2022). Low-dose methylene chloride impairs lysosomal function in human hepatocytes. Cell Biology and Toxicology, 38(6), 875-888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10565-021-09635-2

Johnson, T., Lee, H., & Shaffer, P. (2023). Chronic low-level dichloromethane inhalation induces motor deficits in mice. NeuroToxicology, 95, 109-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2023.03.004